Emile Durkheim, an intellectual giant in the field of sociology, left an indelible mark on the discipline with his revolutionary conceptualization of Social Facts. Rooted in his seminal work, "The Rules of Sociological Method," this extended exploration immerses us in the profound intricacies surrounding social facts, unraveling their characteristics and diverse typologies. As we embark on this intellectual journey, we not only delve into the past but also connect the dots to contemporary sociological thought, emphasizing the ongoing relevance and resonance of Durkheim's groundbreaking ideas.

Social Facts, as articulated by Durkheim, transcend the subjective realm of individual consciousness, representing external, objective realities that shape human behavior and societal structures. This foundational concept encompasses a spectrum of phenomena, including institutions, customs, values, and norms. To fully grasp the profound impact of social facts on society, Durkheim stressed the imperative to recognize their externality — their existence beyond individual awareness.

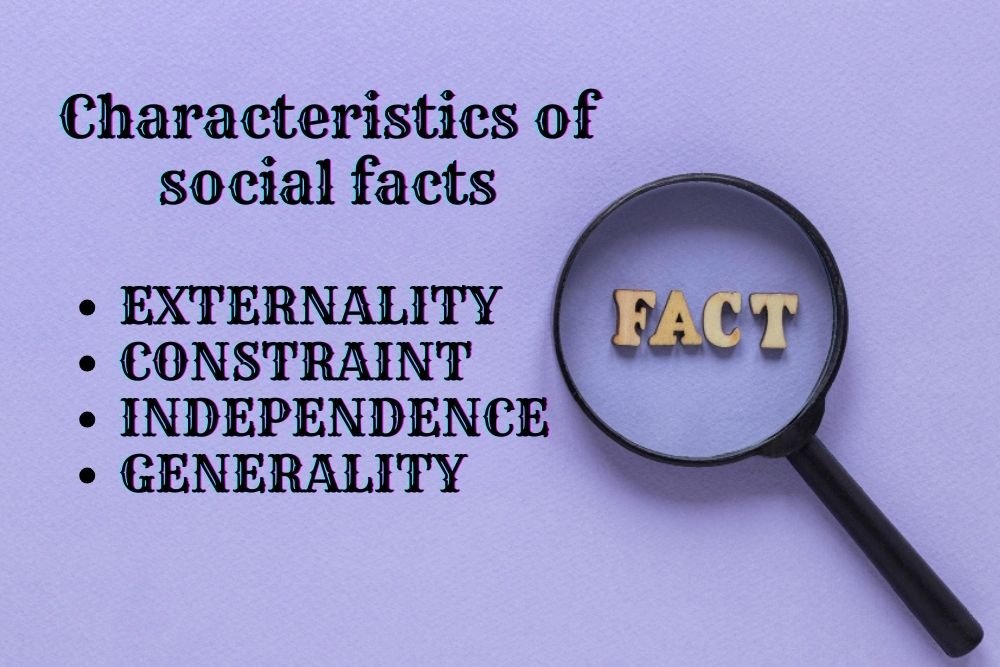

The first salient characteristic distinguishing social facts is their Externality. This attribute underscores the objective nature of social facts, emphasizing their existence outside and their potent influence on individual consciousness. Durkheim's assertion that these external forces exert a constraining effect on individuals spotlights the critical role of social facts in shaping the collective rather than the individual.

Another fundamental characteristic is the Coercive nature of social facts. Durkheim illuminated the inherent coercive power within these external realities, emphasizing their capacity to shape and regulate individual conduct. The norms, values, and institutions encapsulated in social facts serve as formidable social constraints, compelling individuals to conform to established patterns of behavior. This coercive element underscores the sociological imperative to understand the impact of external societal forces on individual agency.

Furthermore, Social Facts possess a General quality, transcending individual cases to manifest as broader societal patterns and phenomena. Durkheim contended that social facts are not confined to isolated incidents but represent generalizable phenomena applicable to a larger social context. This generality magnifies their impact and relevance to the collective societal experience, reinforcing the interconnectedness of individuals within the larger social framework.

Durkheim's categorization of social facts into Normal and Pathological dimensions provides a comprehensive framework for sociological analysis. Normal social facts encompass everyday structures and institutions contributing to social order, while pathological social facts represent deviations that can lead to societal disruptions. Durkheim's exploration of anomie, a state of normlessness and social disintegration, exemplifies the pathological dimension, offering insights into social disorders and their consequences on behavior.

To concretize these characteristics, Durkheim applied his sociological lens to the study of suicide in "Suicide: A Study in Sociology." By scrutinizing suicide rates across different societies, Durkheim showcased how social facts, such as religious beliefs and social integration, exerted a general and coercive influence on individual behavior.

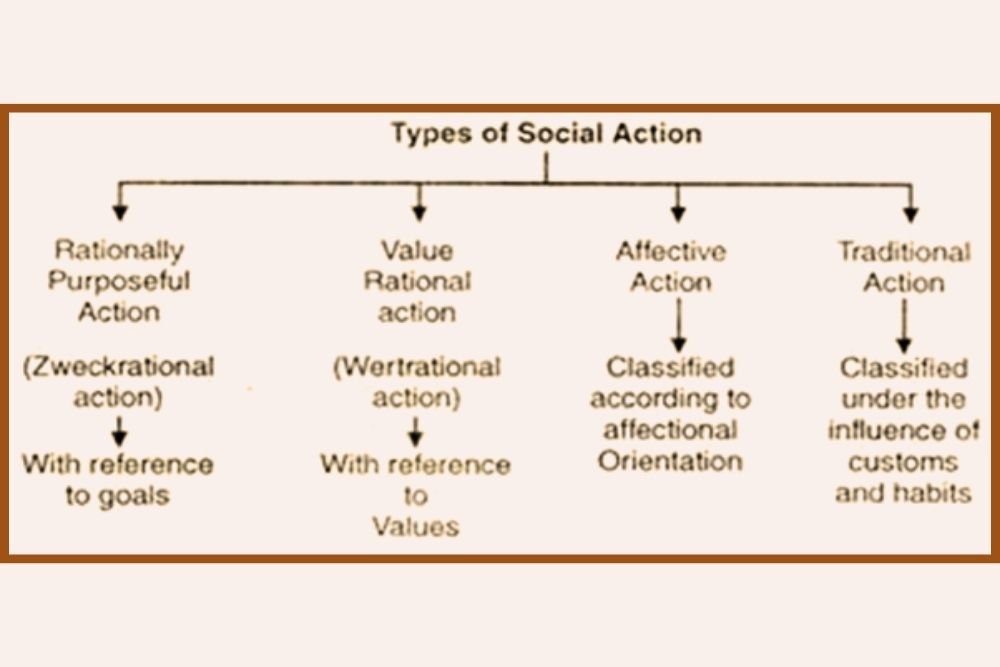

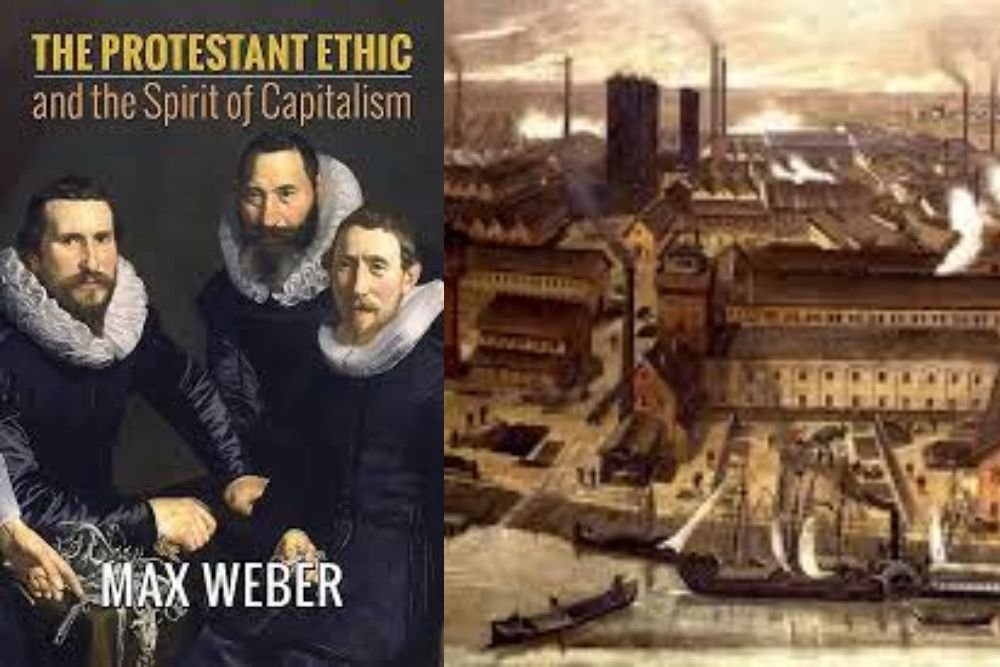

Engaging with Durkheim's ideas, scholars like Max Weber further enriched the discourse. Weber, in "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism," delved into the influence of religion as a social fact on economic behavior. His concept of the Protestant Ethic aligns with Durkheim's notion of external forces shaping individual actions, providing a nuanced perspective on the intricate interplay between religion and society.

Building on Durkheim's foundational ideas, Robert K. Merton's exploration of Manifest and Latent Functions expanded the conceptual landscape. Merton distinguished between the intended and unintended consequences of social facts, offering a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted impacts of societal structures on individual behavior.

In conclusion, Emile Durkheim's conceptualization of social facts as external, coercive, and general phenomena stands as a beacon in the realm of sociology. As we extend this exploration, we not only delve into the past but also connect the dots to contemporary sociological thought, emphasizing the ongoing relevance and resonance of Durkheim's groundbreaking ideas. This expansive journey invites sociologists to engage with the profound intricacies of social life, where social facts weave an intricate web that shapes the collective human experience across time and space.

The multifaceted characteristics of social facts, as unraveled in this exploration, beckon scholars to delve even deeper, fostering a more profound comprehension of the intricate dynamics that govern human societies. Durkheim's legacy continues to guide and inspire, inviting sociologists to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of social facts and their enduring impact on human societies. This enduring journey invites scholars to probe the depths of sociological inquiry, where the interplay between theory and practice shapes our understanding of the intricate tapestry of human existence. Durkheim's profound insights serve as a compass, guiding us through the complexities of social life and challenging us to unravel the mysteries that lie beneath the surface of societal structures.

In embracing this intellectual expedition, sociologists stand at the crossroads of theory and application, poised to contribute to the ongoing evolution of sociological knowledge. As we traverse this vast landscape, the interplay between social facts and human agency unfolds, revealing the intricate dance between structure and individual action. This extended exploration beckons scholars to engage with the richness and complexity of social facts, fostering a deeper comprehension of the forces that shape our collective existence. Durkheim's legacy remains a cornerstone, reminding us that the study of social facts is not merely an academic pursuit but a journey that intertwines with the fabric of our shared humanity.