Sociology, standing at the intersection of empirical inquiry and the intricate dynamics of human societies, grapples with the adoption of scientific methodology. This extended exploration seeks to unravel the multifaceted problems associated with employing scientific methodology in sociology, delving into the complexities and nuances that shape sociological research. Drawing insights from influential scholars and seminal works, we embark on a comprehensive journey through the challenges that arise when scientific rigor encounters the rich tapestry of social phenomena.

-

Reductionism and Oversimplification: Unveiling Layers of Complexity

Scientific methodology, with its structured approach and emphasis on quantifiable data, faces criticism for its potential to oversimplify intricate social realities. Anthony Giddens, in his magnum opus "The Constitution of Society," warns against reductionism, emphasizing the danger of overlooking the depth and richness of human interactions. The intricate layers of societal dynamics, often missed by quantitative analysis, are highlighted by Émile Durkheim's classic critique in "Suicide," showcasing the challenges of reducing the complexity of social phenomena to easily measurable variables.

-

Human Subjectivity and Interpretive Challenges: Exploring the Depths of Experience

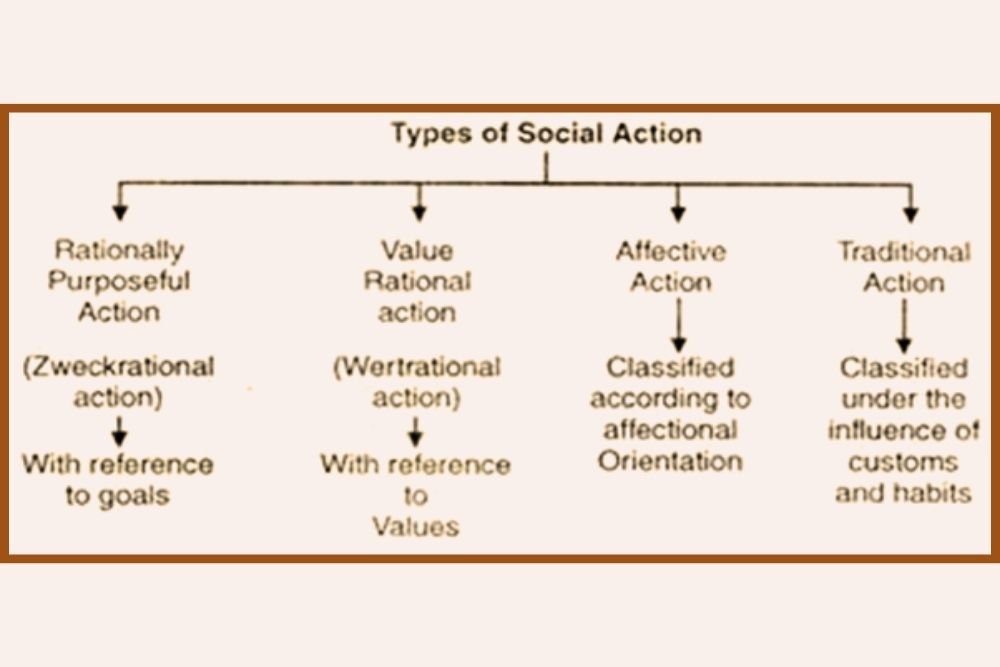

The subjective nature of human experiences poses a formidable challenge to the scientific methodology's quest for objectivity. Max Weber's insistence on understanding social actions through subjective interpretation (Verstehen) sheds light on the limitations of purely quantitative approaches. The call for interpretive methods is echoed by Alfred Schutz in "The Phenomenology of the Social World," advocating for qualitative approaches that capture the intricate subjective meanings individuals attach to their experiences, acknowledging the rich and diverse human tapestry.

-

Value Neutrality and Ethical Considerations: Balancing Objectivity and Responsibility

The pursuit of value neutrality, a hallmark of the scientific ideal, encounters ethical considerations within the realm of sociology. Max Weber's concept of an "ethic of responsibility" underscores the ethical imperative for sociologists to navigate the potential consequences of their research. The ethical dimensions of sociological inquiry, explored by Jane Addams in "Twenty Years at Hull-House," exemplify the need for a delicate balance between scientific objectivity and social responsibility, highlighting the complex interplay between methodological rigor and ethical considerations.

-

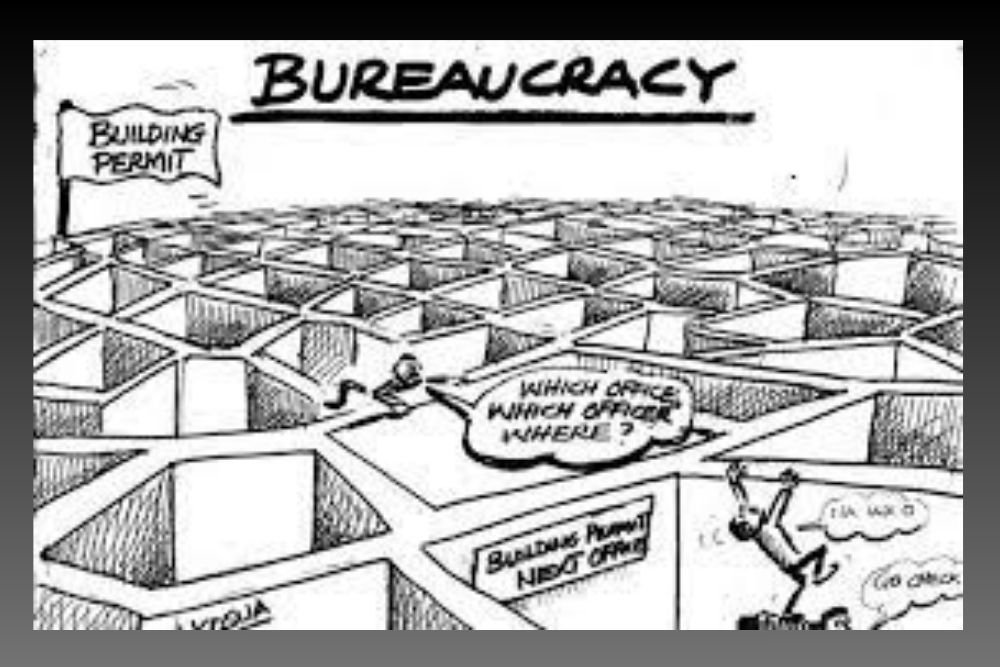

Inadequacy in Studying Dynamic Social Processes: Embracing Societal Fluidity

The dynamic nature of social processes presents a formidable challenge to the scientific method's reliance on controlled experiments. Pierre Bourdieu's critique in "Distinction" underscores the inadequacy of scientific methodology in capturing the fluidity of cultural practices and social dynamics. The limitations of a rigid experimental approach are challenged by George Herbert Mead's symbolic interactionism, which emphasizes the significance of studying social interactions in their natural context to grasp the dynamic and ever-changing nature of societal processes.

-

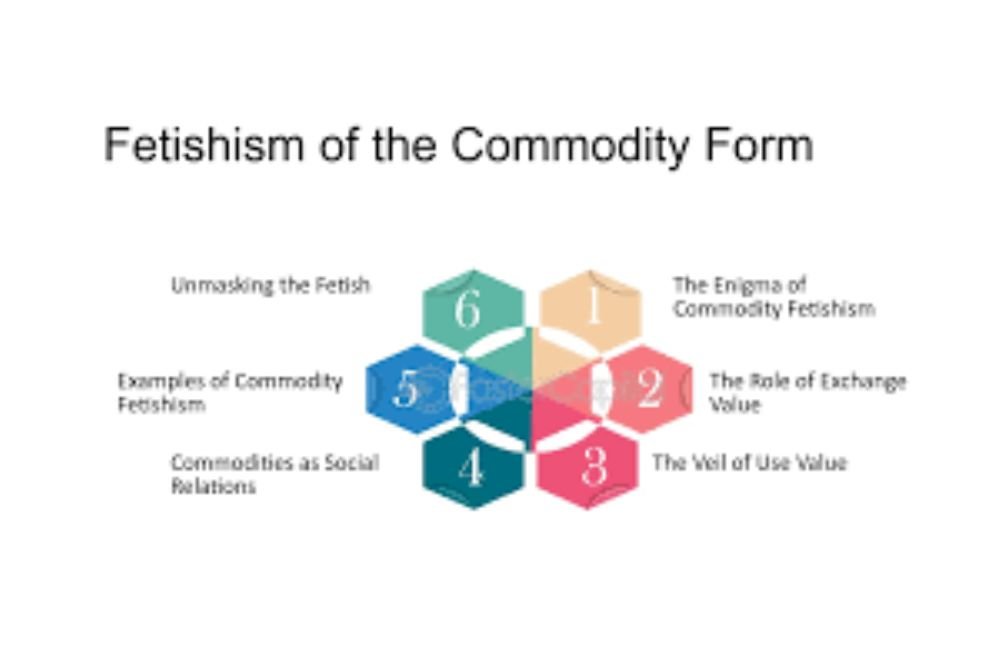

Complexity of Social Reality Beyond Quantification: Emphasizing Qualitative Nuances

Quantifying the inherently complex and multifaceted social reality often falls short of capturing its depth. C. Wright Mills' call for a sociological imagination challenges the reduction of societal problems to individual-level variables. The nuanced perspective offered by Herbert Blumer's symbolic interactionism emphasizes the importance of qualitative methods in capturing the subtleties and nuances of social life, recognizing the limitations of purely quantitative approaches in unveiling the intricate layers of societal dynamics.

-

Resistance to Standardization: Acknowledging Diversity in Research Contexts

Societal contexts vary widely, and attempts to standardize research methods may inadvertently overlook the intricacies of diverse cultures and communities. Amartya Sen's capabilities approach, while rooted in economics, sheds light on the limitations of standardizing well-being assessments without considering the diverse social contexts in which individuals and communities exist. This critique prompts a reevaluation of the assumption that one-size-fits-all methodologies can encapsulate the rich diversity inherent in sociological research.

-

Neglecting the Reflexive Nature of Social Research: Questioning Objectivity

The scientific method often neglects the reflexive nature inherent in social research. Michel Foucault's "The Archaeology of Knowledge" challenges the presumed objectivity in scientific research, urging scholars to critically examine the power dynamics that influence the production of knowledge. The reflexivity embedded in social research, as highlighted by Foucault, becomes crucial in navigating the complex terrain of sociological inquiry, emphasizing the need for researchers to reflect on their own positionality and biases.

In conclusion, the nuanced problems associated with applying scientific methodology in sociology demand a comprehensive understanding. While the scientific method contributes valuable insights, scholars like Weber, Bourdieu, Mills, and Foucault caution against overlooking the complexities, subjectivities, and ethical considerations inherent in the study of human societies. A balanced and reflexive approach, incorporating insights from diverse theoretical perspectives, is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate tapestry of social reality that sociology seeks to unravel.