Positivism, a cornerstone of sociological inquiry, encapsulates a methodological framework rooted in the application of scientific principles to understand and explain social phenomena. The origin of positivism is often traced back to Auguste Comte, widely regarded as the father of sociology. Comte advocated for the empirical study of society, envisioning sociology as a discipline akin to the natural sciences, emphasizing the systematic observation and analysis of social life.

Positivism, as a guiding philosophy, encompasses several defining features that shape its approach to studying society. Central to its methodology is the emphasis on empirical evidence derived from observable and measurable data. This empirical orientation facilitates the identification of patterns, regularities, and causal relationships within social structures and behavior. The reliance on quantitative data and statistical analysis aids in the formulation of generalizable theories and empirical laws governing social phenomena.

The scientific method lies at the heart of positivism. It entails the formulation of hypotheses, systematic data collection, rigorous experimentation, and empirical testing to validate or refute theoretical propositions. This systematic and objective approach aims to establish causal relationships and generate reliable knowledge about the social world.

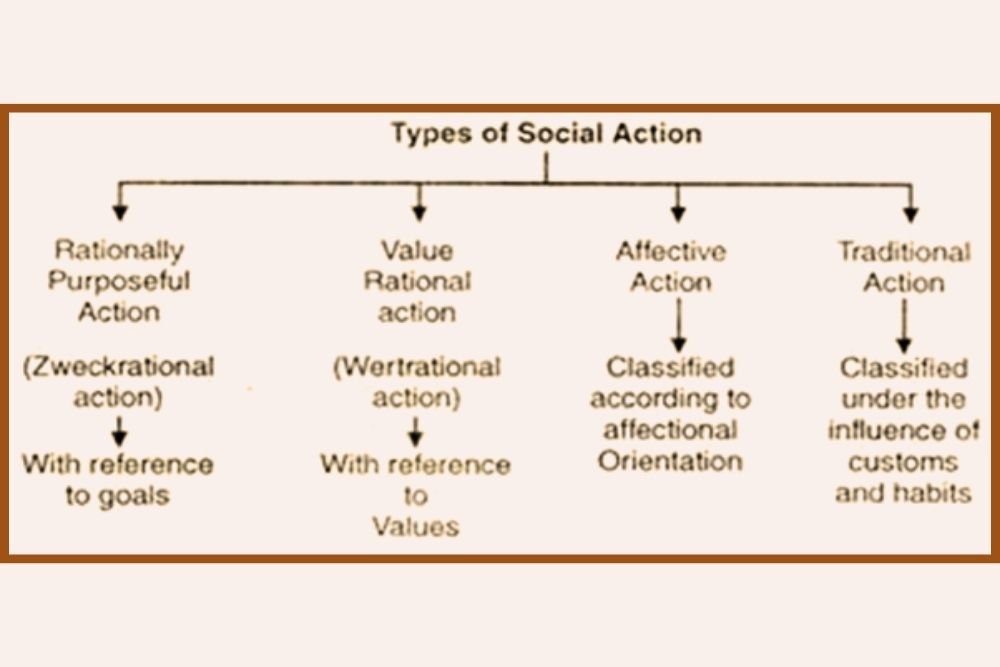

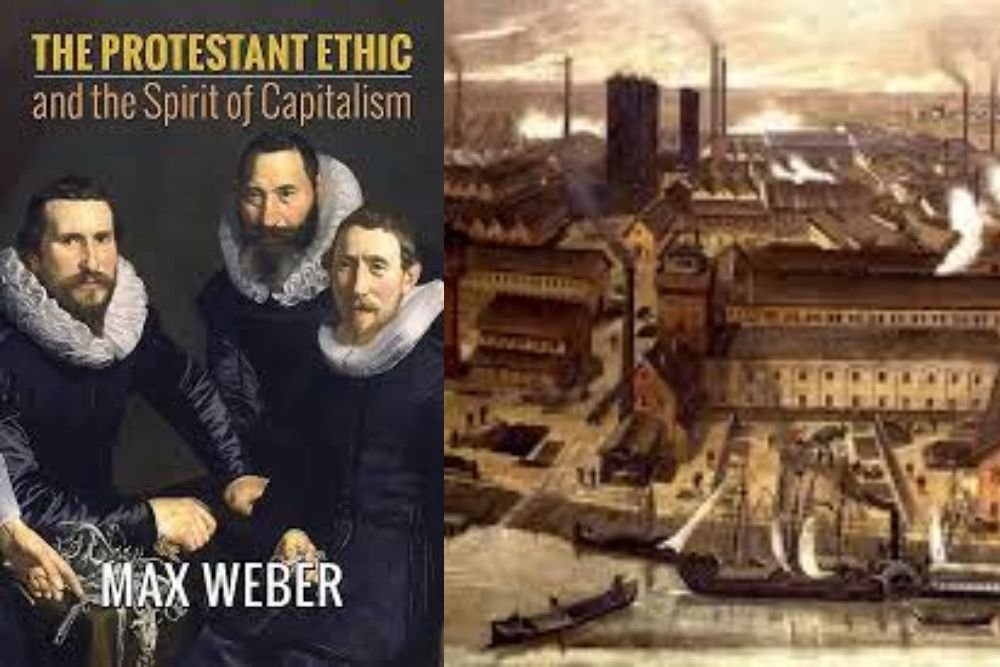

However, positivism has faced criticism within the discipline of sociology. Max Weber, a prominent critic, challenged the positivist stance by highlighting the limitations of reducing social reality to quantifiable data and empirical observation. Weber emphasized the significance of interpretive understanding or Verstehen—the comprehension of social actions and meanings from the perspectives of individuals involved. According to Weber, social phenomena encompass subjective elements such as values, motivations, and cultural meanings that cannot be fully captured through quantitative analysis alone.

Critics of positivism also contend that its exclusive focus on empirical evidence and quantitative analysis oversimplifies the multifaceted nature of social life. The approach tends to overlook qualitative dimensions, including subjective experiences, cultural nuances, and historical contexts that significantly shape social dynamics. Human emotions, symbols, and interpretations often evade quantification, posing a challenge to the comprehensive understanding of complex social interactions.

In response to these limitations, critical theory emerged as an influential alternative to positivism. Scholars like Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse introduced critical theory, which critiques the neutrality of scientific inquiry and emphasizes the interplay of power, ideology, and societal structures in shaping social reality. Critical theorists advocate for a reflexive and multidimensional approach that recognizes the influence of social hierarchies, cultural hegemony, and systemic inequalities on knowledge production and social phenomena.

While positivism remains a significant approach in sociology, its critiques have spurred the development of diverse theoretical perspectives. These alternative frameworks integrate qualitative methods, subjective experiences, and critical analyses, enriching the discipline by offering nuanced understandings of the complex and dynamic nature of human societies.