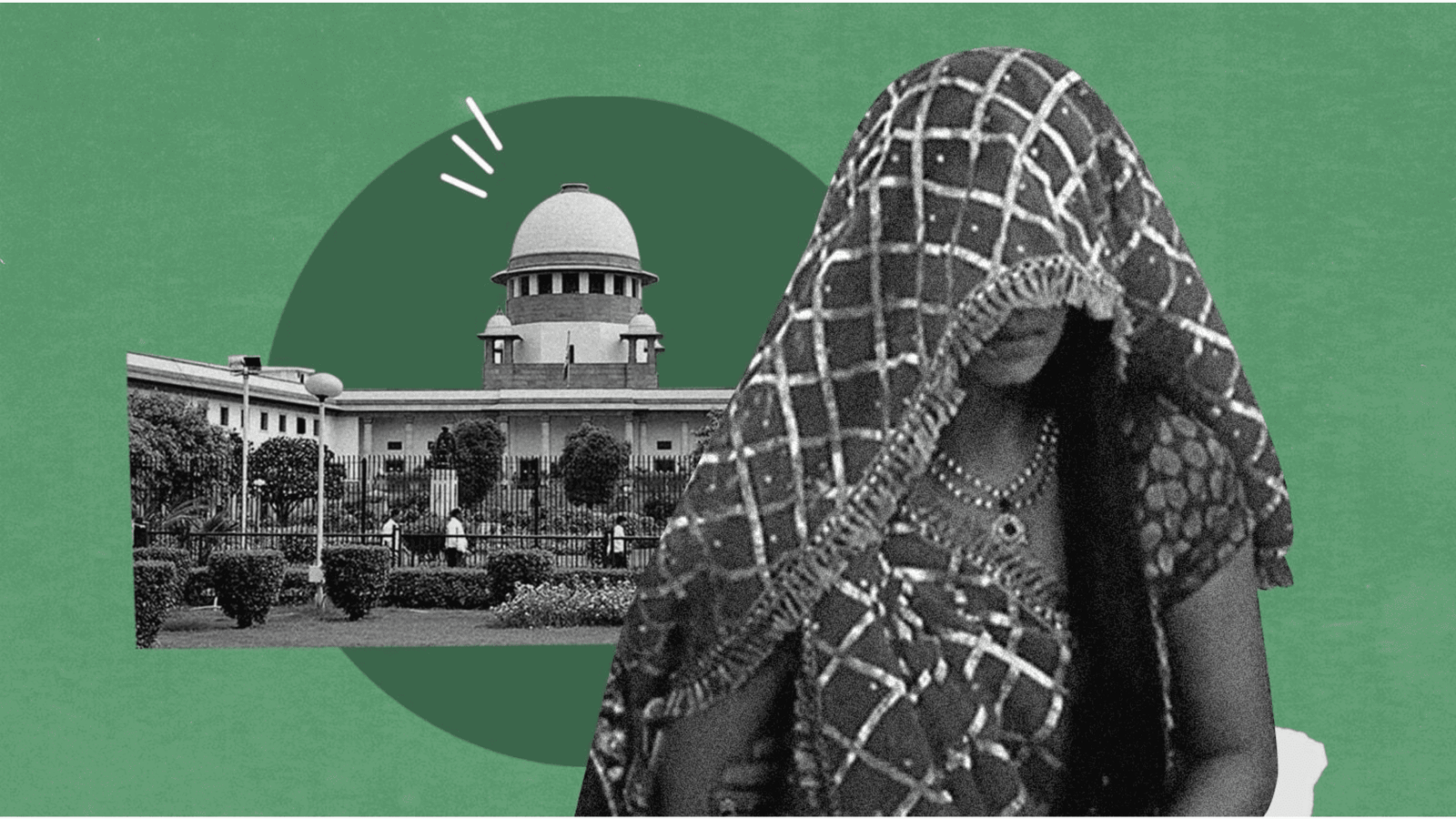

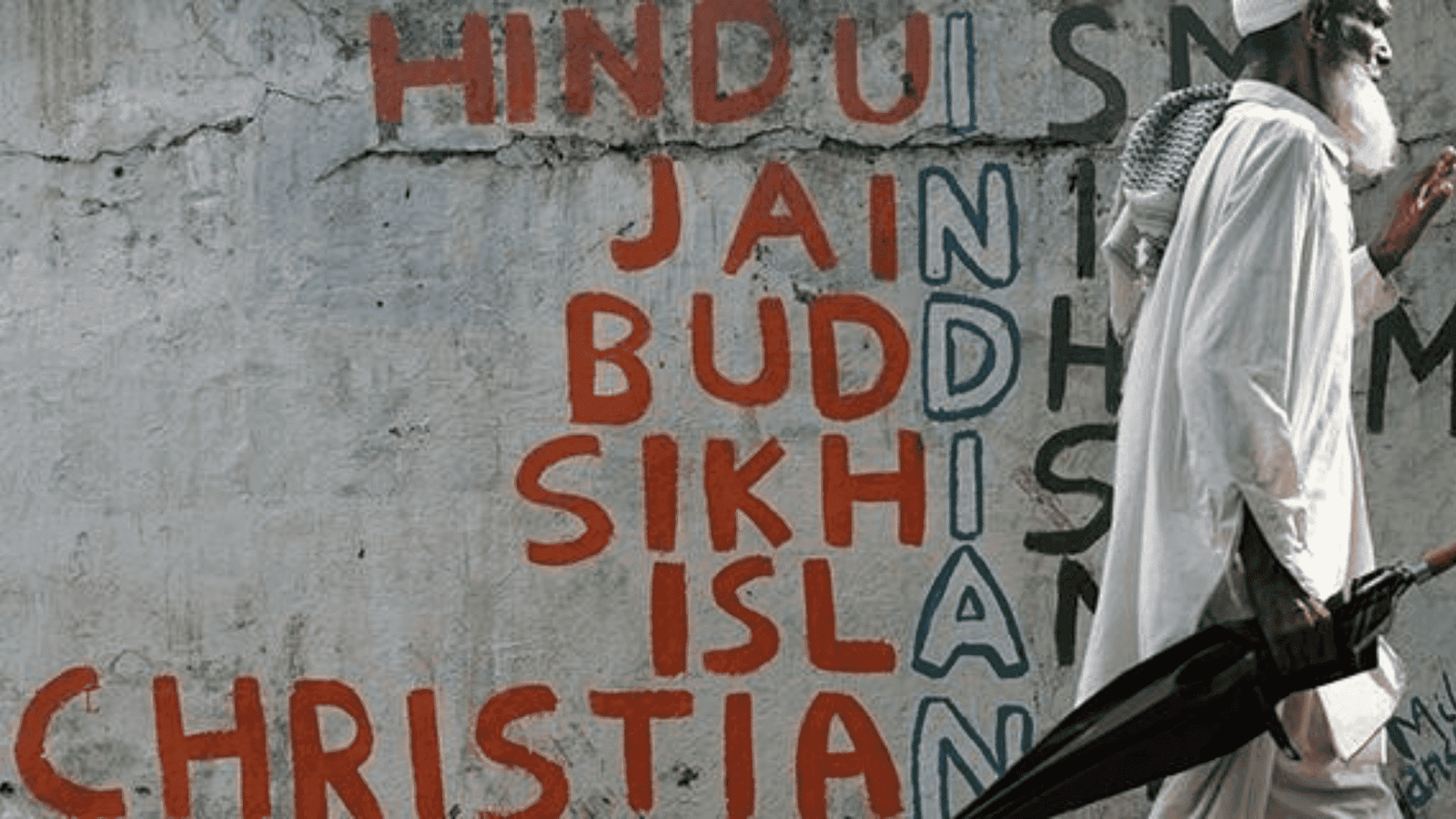

After two years of living behind a mask and trying to decode muffled voices and hidden expressions, one begins to develop empathy for millions of women hidden behind face coverings. Whether they are called ghunghat, pallu, burqa, or hijab, face coverings with varying levels of restrictions are a fact of life for 58 per cent of Hindu and 88 per cent of Muslim women in India. Imposing them on young girls in educational institutions seems particularly worrisome. Hence, one can understand the impulse that drives educational authorities in Karnataka to ban the hijab, although the head covering imposed by hijab is much less restrictive than full burqa or ghunghat. However, external interventions tend to have the opposite effect when it comes to cultural transformations.

The Indian opposition to the colonial Age of Consent Bill, setting the minimum age at marriage to 12 for girls, best illustrates this challenge. Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who was highly progressive in his personal life, summed up his crusade against this law in an 1891 editorial: “We have often pointed out that we are not against the particular reform advocated. Individually, we would be prepared to go even further than what the Government proposes to do. Still, we are certainly not prepared to force our views upon the large mass of orthodox people… We have every confidence that in time most of the reforms now preached would be gradually accepted.”

Demands for veiling in the guise of modesty are unlikely to disappear until women themselves seek change. Arguably, the most impressive demonstration comes from Haryana. In a state known for its solid adherence to ghunghat, a quiet revolution began a few years ago when Manju Yadav, a schoolteacher, started a campaign to get women leaders together to cast off their ghunghats. This campaign faced initial hurdles but gained momentum when one of the largest khaps, the Malik Gathwala Khap, asked women to give up ghunghat.

However, mobilising to protest veiling is not easy in the Muslim community. Sania Mirza has faced considerable criticism from fellow Muslims for refusing to play tennis while being covered head to toe. Shabana Azmi was told to stick to singing and dancing by clerics for seeking a debate on whether face covering was ordained by Quran.

Ironically, gender seems to be a crucial battleground for the culture wars, making for strange bedfellows and creating situations that make the oppressed complicit in their own subjugation. Demanding freedom from oppressive gender norms requires release from external pressures that force women to choose between their gendered interests and banding together to protect their communities.

As Flavia Agnes notes, following the anti-Muslim riots in Mumbai, Muslim women’s groups found themselves cancelling anti-domestic violence programmes for fear of providing additional ammunition to the police to harass Muslim men. The Karnataka hijab incident has framed the debate in such a way that the lawyers for the plaintiffs, the media, and civil society at large, portray the hijab as being a central tenet of Islam and, hence, protected from control by educational authorities. This unfortunate conflation between religion and dress code will make it difficult for Muslim women to follow Najma Khan, pradhan of Dhauj village in Haryana and a member of Manju Yadav’s movement, in casting off their veils.

.Education is a crucial resource in women’s ability to resist oppressive gender norms. Whether among the Hindus or the Muslims, data suggests that education is associated with a lower prevalence of purdah or ghunghat. About 67 per cent of women with less than a Class V education practice ghunghat or purdah compared to 38 per cent of college-educated women. However, requiring the abandonment of the hijab to obtain education puts the cart before the horse. For Muslim girls, this is a troublesome development. The National Statistical Office estimated gross attendance ratios in secondary education for Muslim women to be 43 per cent compared to 63 per cent for all Indian women. The education systems should be doing all they can to encourage participation among Muslim girls rather than placing obstacles in their way.

The timing of the hijab storm in Karnataka is regrettable. Schools and colleges have been closed for nearly two years. Returning to education will be difficult for all students, most of all for those already falling behind in learning. Data from the India Human Development Survey, conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research and the University of Maryland, shows tremendous inequalities in learning outcomes among various social groups. Whereas 68 per cent of forward caste children aged 8-11 can read a short paragraph, the proportion is barely 47 per cent for Muslim children. These inequalities are likely to have been exacerbated as students struggled to learn on their own during the lockdown. At a time when schools and colleges need to focus on bringing children back to classrooms and helping them overcome the learning deficits that are likely to have accumulated, the diversion created through the hijab controversy is counterproductive for all students, most for the students who were already burdened by the learning gaps.

It is time for us to focus on empowering all women, including Muslim women, by ensuring their access to education, employment, and public safety. With enhanced power will come increased agency to transform gender norms if and when women themselves choose to do so.