Ninety nine percent of sexual assaults in the country go unreported.

Women make up only 7.28% of India’s police force. Of these women, 90% are constables, while less than 1% hold supervisory positions, according to the recently released “Status of Policing in India Report, 2019”. The numbers are low despite 20 states having reservations for women in the police.

This skewed ration is “leading to impediments in effective implementation of the legislations on crimes against women”, noted a Ministry of Home Affairs circular in 2015.

Even after they make it to the police force, women run into hurdles. They are likely to face gender bias and report high levels of job dissatisfaction, according to the policing report released by Common Cause, a civil society organisation that advocates for human rights, and the LoknitiProgramme of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, a research institute supported by the Ministry of Human Resources and Development.

The researchers surveyed nearly 12,000 police personnel, across 21 states. More than 2,000 of these police personnel were female, about 20% of those surveyed. This was deliberately higher than the representative 7% so the researchers could have enough responses from female personnel to analyse separately.

The study is a companion to the 2018 Status of Policing Report, which surveyed more than 15,000 respondents in an attempt to understand citizens’ perceptions of the police.

The two reports taken together paint a clear picture of the status of women in the police force, the attitudes towards them, and how this affects policing.

Why are women police important?

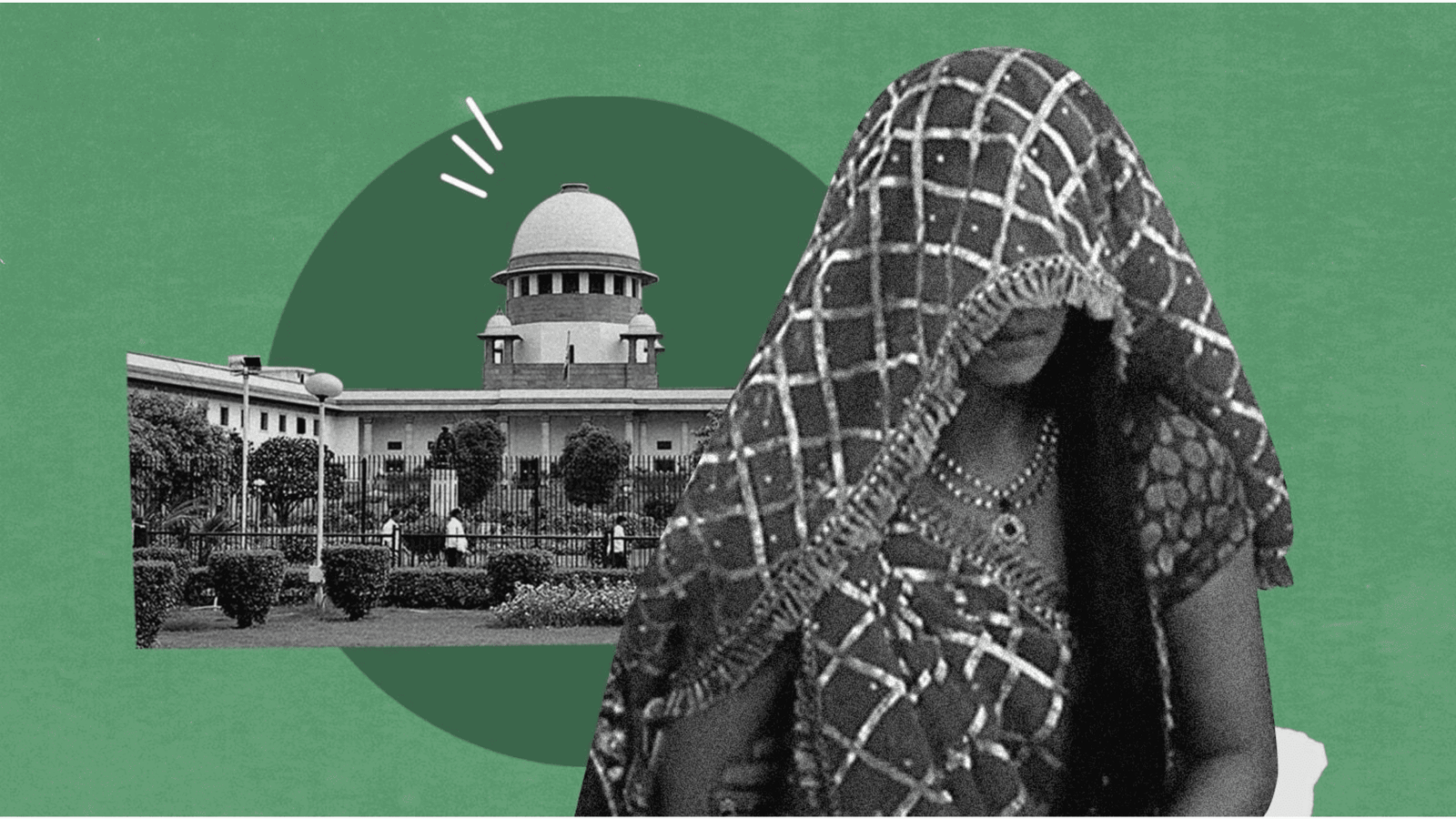

“Data from 39 countries show that the presence of women police officers correlates positively with reporting of sexual assault, which confirms that recruiting women is an important component of a gender-responsive justice system,” noted a United Nations Women report in 2011-’12 titled “Progress of the World’s Women: In Pursuit of Justice”.

Approaching male police officers can be difficult for women, the report said. In fact, both male and female victims of sexual violence expressed a preference for reporting to women police.

In India, the National Family Health Survey of 2015-’16 said that 99% of sexual assault cases go unreported.

A rise in the number of policewomen has been correlated with a decline in rates of domestic abuse and intimate partner crime.

Policewomen are less likely to have allegations of excessive force against them, and their presence can reduce the use of force by other police officers, according to the Status of Policing 2019 report.

Why are there so few women in the force?

“There is a strong belief that combat, by nature, is a male occupation; that the police force is a male domain and therefore unsuitable to the female physique and temperament,” says the 2018 report on citizens’ attitudes towards the police. These sentiments mean that most women do not even apply for jobs in the police, believing themselves unsuitable or because of family pressure against such a career.

One in two of respondents told researchers that women were unsuitable for police work because they lack the physical strength to do so. About the same ratio of people also believed that the inflexible working hours were a deterrent. Women were as likely to hold these opinions as men, although younger women and city dwellers were more favourable to the idea of women in the police.

Policing while female

The researchers found that female police personnel were more likely to do in-house tasks that did not require them to leave the station. They maintain registers, file FIRs, deal with the public and do other tasks while their male counterparts conduct investigations, patrol, and provide VIP security.

One in five women police personnel reported not having a separate toilet for women at their station. In Bihar and Telangana, that ratio was three in five. A fourth of policewomen also reported that there was no sexual harassment committee at their workplace, despite such a committee being mandated by the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act of 2013.

Policing has traditionally been considered a male job, and both men and women hold patriarchal ideas about women’s capabilities in this field, the report said. Their views by-and- large mirror the views held by citizens, although women in the police underestimate themselves less. Bihar, Karnataka and West Bengal have the highest levels of bias against women in the police force.

These attitudes carry over to policing, which is why nearly one in five personnel believe that gender-based violence complaints are false and motivated to a very great extent. There is some merit to the idea of false rape cases being lodged, for instance by the parents of girls who have eloped, or in the case of a breach of promise to marry. But given the vast prevalence and under-reporting of violence against women, the disbelief of police personnel towards such complaints only discourages victims from seeking remedy.

Another important point the researchers make is about attitudes towards transgender people. While the first transgender police officer – recruited in Tamil Nadu in 2017 – made headlines, the police still has a long way to go in eliminating prejudice towards people outside the male-female gender binary. Thirty five percent of police personnel said that transgender people were very much or somewhat naturally prone to committing crimes.

The way forward

The researchers note that an increase in policewomen will also go a long way in making police stations more accessible for women. Meeting reservation quotas for women would be a first step towards creating a more equal police force.

Regular gender-sensitisation training for the police would also help undermine patriarchal attitudes. The study found that only a third of police personnel had received such training over the past two or three years.

A gender-inclusive force will be more representative of and responsive to the population they police.