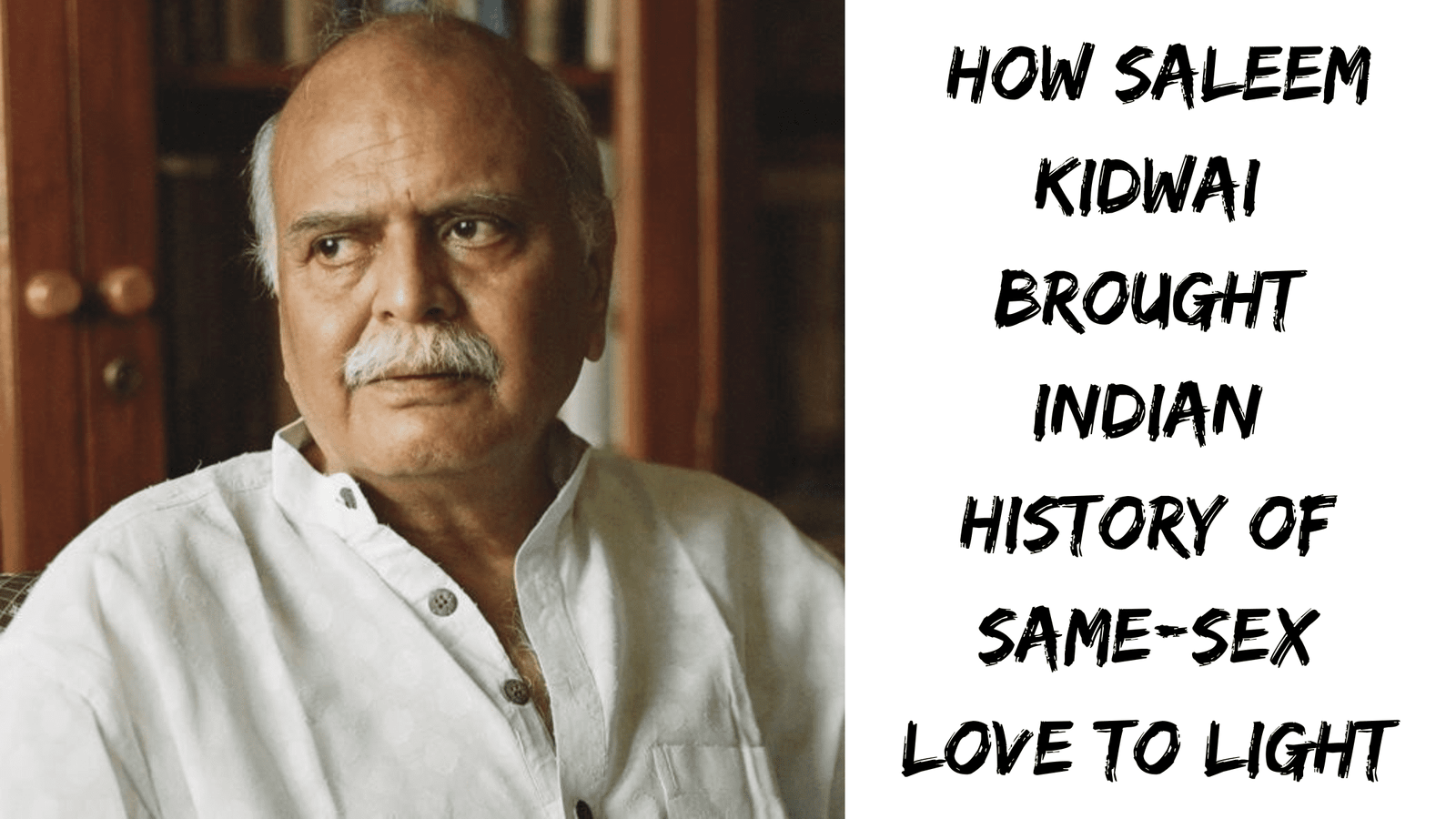

His mobilisation of LGBTQIA+ community into a movement for freedom, as well as his literary achievements, especially in translating Urdu works, are admirable

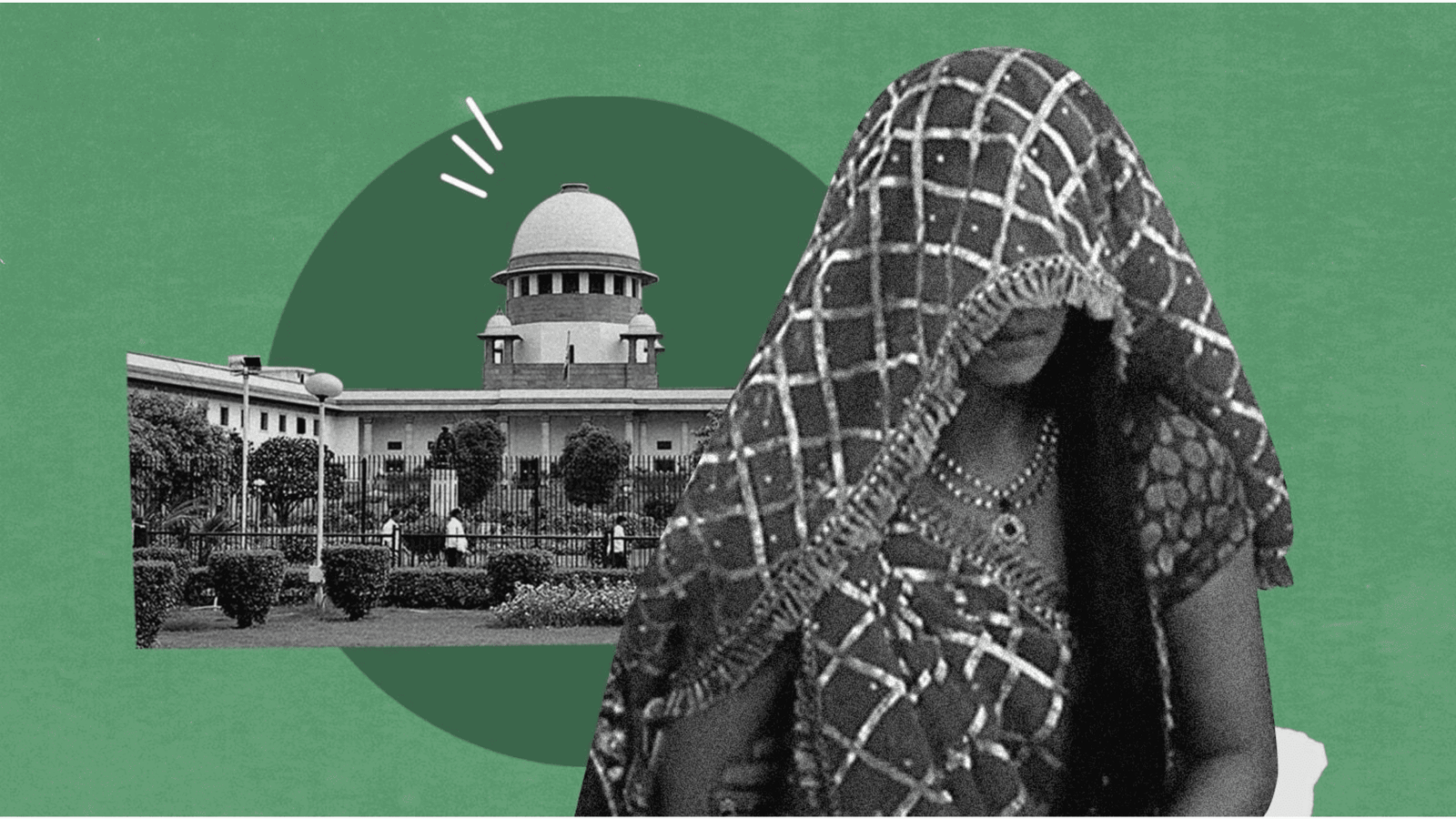

I must admit I did not expect such a storm of news, obituaries and voices claiming friendship, coming from all directions within minutes of Saleem Kidwai’s death. I knew him as a great intellectual, a committed historian and a scholar with deep interest in Urdu Literature, and someone, who despite his achievements remained humble. He was the one responsible, in some ways, in mobilising the LGBTQIA+ community into a movement for “freedom”. He was one of the first academics to come out openly as a member of the then-condemned community. That required courage and honesty. He used his research-oriented brain and scholarly patience to dive deep into two millennia of history to trace instances of same-sex love, and together with Ruth Vanita, wrote a book which not only became an instant classic but was responsible, to a great extent, for the removal of Section 377 from the Indian Penal Code by the Supreme Court. That was no less an achievement. It brought a smile on the face of the 21st century because it was an important social change for India.

Saleem studied and lived in Delhi from the age of 17. He also went to Montreal for his undergraduate studies, and later taught Medieval History at Ramjas college till 1993. He loved his profession as a teacher, but he also loved his independence. Urdu literature interested him, too. His love for Urdu poetry attracted him towards Begum Akhtar’s ghazal singing. He had great admiration for her. He was influenced by his mother’s interest in Urdu fiction. He once told me, “one of the authors my mother used to read was A R Khatoon,” a name which has escaped many an avid Urdu fiction reader’s memory today. Saleem was convinced that Urdu literature had a treasure to offer, but the readership of that language having dwindled, many of the interested lot are left deprived. He didn’t sit back and sulk, but started on his new mission of translating the works of his favourite author, QurratulainHyder. That was no easy task. But he loved taking challenges. He had earlier translated Malika Pukhraj’s memoir which he named, Song Sung True. QurratulainHyder needs no introduction, but few know that she preferred to translate her works herself, because she felt that no one else could do justice to them. Among the works she left untranslated were Chandni Begum, her last novel, and Safina-e Gham-e- Dil, her second novel, written in 1952.

Both were translated by Saleem Kidwai and were showered with critical acclaim. Safina-e-Gham-e-Dil, which he named Ship of Sorrows, was a far greater feat of translation, because it is a novel where Hyder, influenced by European Modernists, was at her experimental best. She was trying literary techniques which she would later use in her magnum opus, her much-acclaimed Aag Ka Darya (River of Fire).Those who have read the original Safina-e-Gham-e-Dil will appreciate that to translate it in English was intensely difficult. Saleem did it with excellence. In the interval between the two novels by Hyder, he translated Aaina-e-Hairat, a rare book of short stories about animals, written in the early forties, by Syed Rafiq Hussain. He called it A Mirror of Wonders.

Coming back to his contribution to the “freedom struggle” of the LGBTQIA+ community, it was the book Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History, co-authored by him and Vanita, which gave the movement strength, and a reason to the cause. In a frank interview after Section 377 was struck down, Kidwai said that he had been taking notes and preserving cuttings about same-sex love for a long time. When he got to know that Vanita was involved in a similar exercise, they decided to exchange notes, and that’s when the serious research for the book started. The book is based on strong empirical evidence from early Puranic period about the celebration of same-sex love across India over the last two millennia. In India, it was outlawed in 1861 by the British when they included Section 377 in the IPC. The book busts the myth that same-sex relationships are a recent import from the West. It was the British who came armed with their Victorian morality, and introduced the Indian Penal Code in India.

In their own country, the British convicted some of the best brains for homosexuality. Oscar Wilde was thrown into the horrible Reading Gaol, in the mid 1890s, and an unbearably cruel punishment was meted out to Alan Turing, a top British mathematician and logician for the same “crime” in 1952. Despite his many path-breaking contributions, Turing was given 12 months of hormone therapy, after which he met a mysterious end. At the beginning of the 21st century, the British government woke up to apologise for the “utterly unfair treatment” to Turing.

Saleem Kidwai had realised early in life that he should not lead a clandestine life nor allow friends who shared his leanings to nurse a guilt. He encouraged them to contact and find members of their community, get together, and then ask for their rights. Individuals, by themselves, have no say in any matter. To crown it all, he worked hard with someone, who had the same cause, and produced a book which did wonders.