Social distancing set in motion an illness whose vaccine we still have not been able to – or wished to – discover. Caste, like a virus, has the virtue of self-duplication inherent in it.

According to the thesis on the origins of castes that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar put forth in his remarkable essay Castes in India, it was the Brahmins who formed the first group of people who “enclosed” themselves – or, socially distanced themselves, to use a current phrase – from others around them.

“At some time in the history of the Hindus, the priestly class socially detached itself from the rest of the body of people and through a closed-door policy became a caste by itself,” Ambedkar notes in the essay.

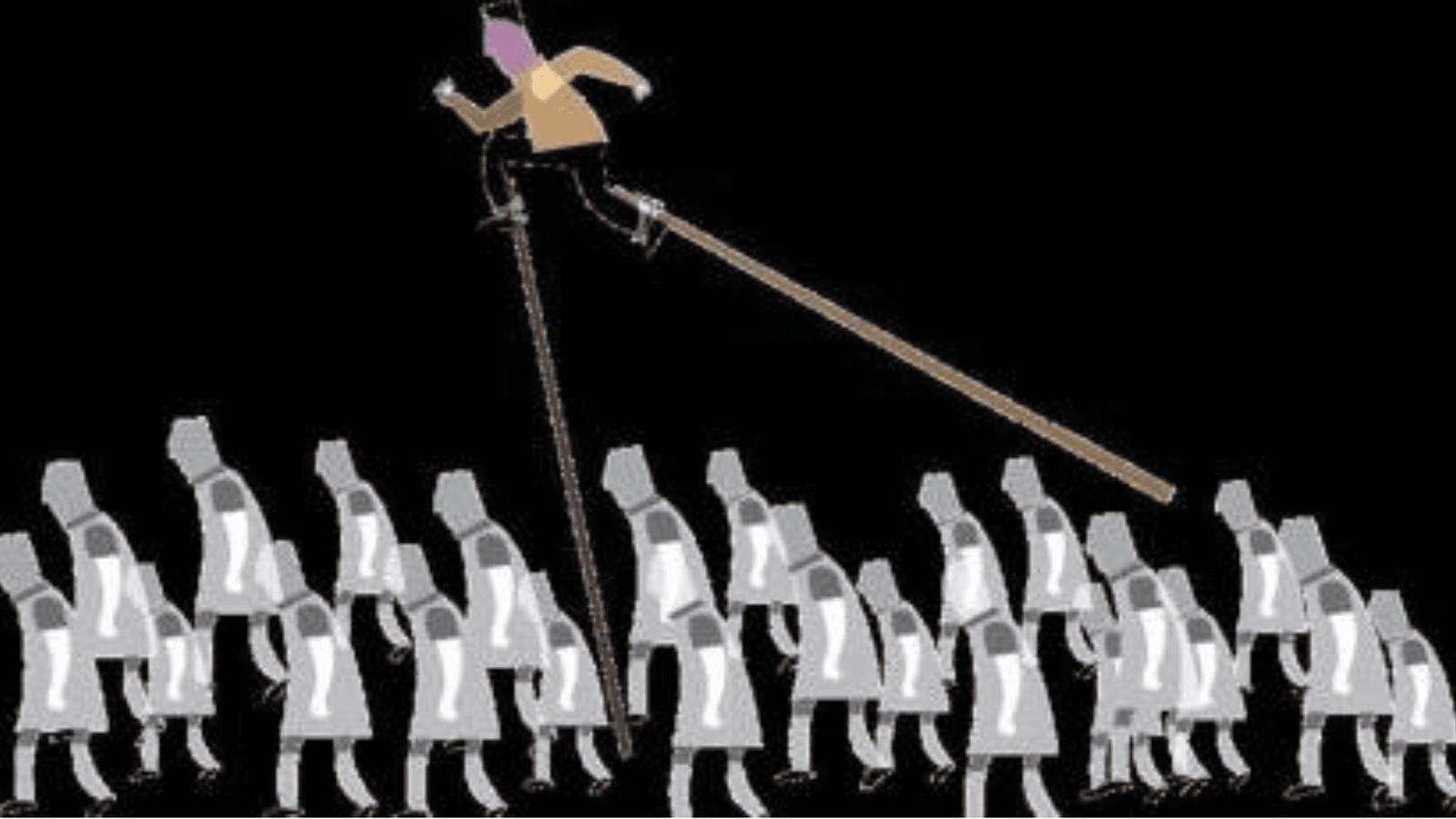

That the castes were believed to be a part of a “graded hierarchy,” to use Ambedkar’s term, was itself an effort to institutionalise and proclaim social distance. It was a social distance which was inscribed in sacred texts and gradually in people’s minds and practices.

His further description in the essay of the way castes spread and multiply eerily resembles the propagation of some viral pandemic: “Now apply the same logic to the Hindu society and you have another explanation of the ‘fissiparous’ character of caste, as a consequence of the virtue of self-duplication that is inherent in it.”

According to the thesis on the origins of castes that Dr. B.R. Ambedkar put forth in his remarkable essay Castes in India, it was the Brahmins who formed the first group of people who “enclosed” themselves – or, socially distanced themselves, to use a current phrase – from others around them.

“At some time in the history of the Hindus, the priestly class socially detached itself from the rest of the body of people and through a closed-door policy became a caste by itself,” Ambedkar notes in the essay.

That the castes were believed to be a part of a “graded hierarchy,” to use Ambedkar’s term, was itself an effort to institutionalise and proclaim social distance. It was a social distance which was inscribed in sacred texts and gradually in people’s minds and practices.

His further description in the essay of the way castes spread and multiply eerily resembles the propagation of some viral pandemic: “Now apply the same logic to the Hindu society and you have another explanation of the ‘fissiparous’ character of caste, as a consequence of the virtue of self-duplication that is inherent in it.”

Caste, like a virus, has the “virtue of self-duplication…inherent in it,” according to Ambedkar’s astute observations. The Brahmins instituted social distancing first, which it seems, led to the (caste) pandemic – an order of things slightly different from the way things are developing in the novel coronavirus pandemic.

At any rate, the social distancing established by the Brahmins resulted in very real consequences, especially those of untouchability and even unseeability.

There were, for instance, concrete interdictions in certain places in India against even the shadows of untouchables falling on the upper castes. So, between certain times of the day when the shadows lengthen, the former were not allowed within certain cities in India.

This segregation implicit in the system of untouchability was characterised by Ambedkar in a manner that resonates with the narrative around social distancing and the coronavirus today. In his work Who Were The Untouchables, he states:

“It is not a case of social separation, a mere stoppage of social intercourse for a temporary period. It is a case of territorial segregation and of a cordon sanitaire putting the impure people inside a barbed wire into a sort of a cage. Every Hindu village has a ghetto. The Hindus live in the village and the Untouchables in the ghetto.”

One must note the usage of the term cordon sanitaire employed by Babasaheb in connection with caste untouchability – and mark its most recent usage in Time magazine’s reference to the coronavirus outbreak:

“When the Chinese government effectively cut off some 50 million people in Wuhan, the location of the first outbreak, that was most aptly described as a cordon sanitaire. That French term, which came into use following the flu pandemic of 1918, describes roping off a whole community, which might contain sick and healthy people, and preventing anyone from leaving in order to curb the spread of a disease.”

Dr. Ambedkar was spot on, employing a French term equivalent to something like a quarantine but, characteristically, imparting it a stronger and more dire meaning than that associated with a mere quarantine. In his words, it denoted a life-long segregation and a “roping off” of an entire people as if they suffered from a disease.

The academic, Gopal Guru, in his essay The Archaeology of Untouchability, lists the names given to the actual instances of social distancing and the segregation that occurs throughout India to isolate the so-called untouchables into separate areas:

“Since the untouchable was a walking danger, there was a need to quarantine this danger in an isolated place called the Chamrauti in Uttar Pradesh, Halgeri in Karnataka, Cherry in Tamil Nadu and Mahar/Mangwad in Maharashtra.”

Guru too cannot stop himself from employing medical terms such as ‘quarantine’ to describe the isolation of the ‘danger’ posed by the untouchables.

In the book The Cracked Mirror co-authored by him, Guru provides an interesting view on how Mahatma Gandhi did not have to face issues of social distancing when he travelled through India – and thus did not experience a socially discriminatory India – but Ambedkar did:

“It is therefore no wonder that Gandhi does not discover India as ‘Bahishkrut’ because his voyage makes him open up in a kind of sameness where he, by and large, finds himself in the midst of peasantry but residing with the families of the feudal lords and the emergent industrialist. Occasionally, as politics demanded, he also stayed for a brief while in the hut of the scavenger. Gandhi thus had a choice to ‘transgress’ spaces vertically.

Ambedkar did not have this choice. He and his social constituency open up only horizontally, moving from one dalitwada to another across the region.”

In fact as Dr. Ambedkar himself goes on to show in The Untouchables, there is the sense of physical distance in some of the very terms used for those considered Untouchable, such as antyaja and antyavasin: those people living at the anta or end of the village.

Even the term avarna or those without a varna only served to put the Untouchables beyond the pale of the varna system – a metaphorical social distancing that consigned fellow human beings farthest away in social hierarchy.

Social distancing was also a key factor in denying the lower castes benefits of learning, which initially took the form of Vedic learning. “For a Sudra is (like) a cemetery, therefore the Veda is not to be read in the vicinity of a Sudra,” is a commonly found injunction in several Brahminical law-books warning against the recitation of the Veda near a Sudra.

In his classic tract Annihilation of Caste (AoC), Ambedkar lays out his understanding of an ideal society, centred around ideas of fraternity: