There is uproar following the revelations of the Pegasus Project, but surveillance as a method of control has existed since Jeremy Bentham’s age. How it evolved into its current digital form and what the future could look like are questions that need greater discussion. The situation must be placed in a historical context should be understood as being derived from the chain of ideas originating from Bentham’s panopticon. The panopticon was theorised as a system of control and surveillance by Bentham in the 18th century. The idea behind the structure was to allow prisoners in their cells to be observed by a single guard, without them being able to tell whether they are being observed. The key difference between this idea and the current form of digital surveillance is that of tangibility. The relative intangibility of data surveillance risks its normalisation. While with Bentham’s panopticon there is a sense of physical exposure before authority, the same cannot be felt when we are navigating data in our private spaces. Emphasis on national security concerns also contributed to the normalisation of surveillance.

In the long history of surveillance, the state has always played a central role. The first breakthrough event at the intersection of privacy, technology and surveillance was the 1844 postal espionage crisis in Britain. Rowland Hill’s invention of the Penny Post was aimed at promoting cheap and secure communication. It was when Italian republican Giuseppe Mazzini discovered that his postal correspondences were being subjected to state interception, that a “privacy panic” was unleashed. However, no significant step was taken in this regard until, in 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis provided the foundation for a conception of privacy that can be equated to control over information about oneself.

As argued by sociologist David Lyon, the spread of technology within societies will lead to their increased surveillance and subsequent lack of privacy. In the late 20th century, the internet was invented as a Cold War communication network. This led to the creation of the Internet of Things [IoT] which allowed surveillance to be embedded in all objects, from fridges to cars. Data began to be “skimmed off” from everyday practices such as shopping. The resurgence of neoliberalism in the 20th century meant that public-private partnerships which had only been developing since the 1980s became commonplace. Thus, a new player of commercial corporations was added to the existing relationship between the state and surveillance. This is mirrored perfectly in the current context of Pegasus. Developed by a private company, it has become a favourite tool for state surveillance.

Privacy expert Daniel Solove recognised that new technologies can lead to a panoply of new privacy harms. Pegasus too is a by-product of the advancing technology and seriously intrudes upon one’s private affairs. As William Prosser stated, protection against such intrusion is a facet of privacy. It is only in the recent legal context that privacy began to be increasingly viewed as a constitutional right. In fact, various international treaties and conventions explicitly embody this right. Due to the relatively nascent nature of this right, the tendency to not view privacy as intrinsic to one’s person remains. Oftentimes, we do not expressly feel violated without an explicit sense of physical exposure. Perhaps such notions ultimately fuelled the rise of the large network of state-controlled digital surveillance that exists worldwide today.

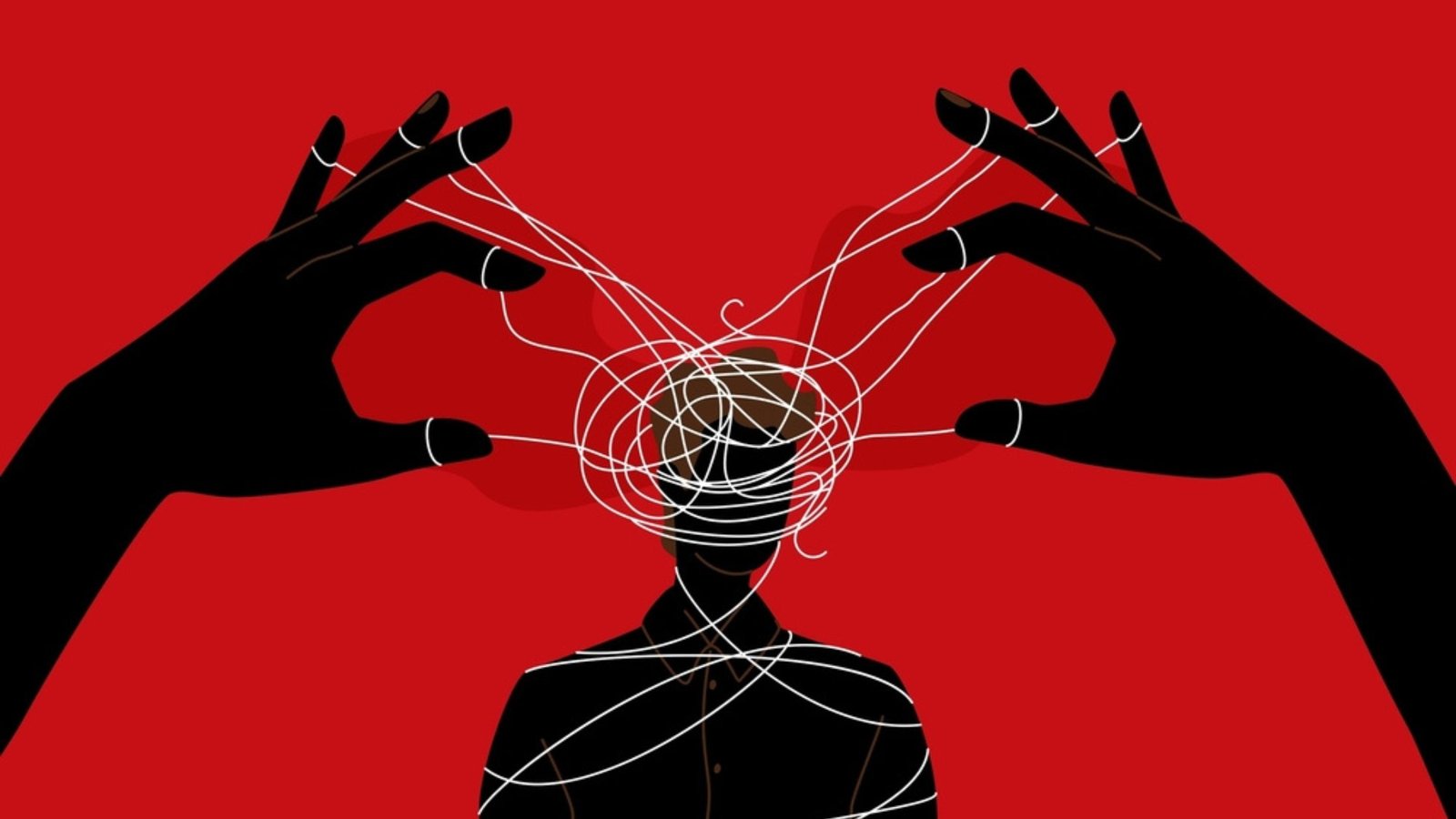

Michel Foucault described the prisoner of a panopticon as being at the receiving end of asymmetrical surveillance: “He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication”. Essentially, he believed that the prisoner is seen constantly and information about him is always available without any communication.

Historic panopticism is reflected in the example of the establishment of colonial rule in 19th century Egypt. Panoptic modalities of power were enforced at all levels of society, with individuality stripped away. The villages were centralised and that made it simple for the government officials to track the activities of the people. Here, the gaze was a very physical and tangible one. However, Foucault states that acquiring such control does not require physical domination, but thrives on the possibility of observation. It is in this context that he theorised the concept of panopticism, where the “watcher” ceases to be external to the “watched”. The constant gaze of the watcher becomes internalised to an extent where every prisoner becomes their own guard. Foucault argued that this phenomenon could lead to the possibility of the state carefully fabricating the behaviour of the individuals. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, Foucaulist ideas were used by factory owners to encourage self- surveillance amongst the workforce. This reduced costs as the workers would constantly correct their own behaviour to fit their prescribed functions. As George Orwell wrote in 1984, “The hypnotic eyes [of Big Brother] gazed into his own. It was as though some huge force were pressing down upon you — something that penetrated inside your skull, battering against your brain, frightening you out of your beliefs, persuading you, almost, to deny the evidence of your senses.”

To Foucault, knowledge is a form of power and thus, knowledge about a person gives us power over that person. The personal data collected by the state is capable of moulding and affecting our decision-making processes and behaviour. This can then be used as a tool of oppression and control and the rise of a “Big Brother” State, as Orwell puts it. A potential implication could be a stultifying effect on the expression of dissent and difference of opinion, which no democracy can accommodate.

Looking at the enormous backlash against the Pegasus Project from across the world, it can be said that there is a growing push for what can be termed as “bottom-up surveillance”. With powerful entities exercising control over individuals’ personal data, individuals may argue that they too can watch back. The demands of these people are based on the fact that one’s privacy and freedom cannot be taken for granted and that democracy cannot sleep while surveillance flourishes. This leads to the creation of an inverse panopticon.

This leads us to Thomas Mathiesen’s synopticon. He used this concept to refer to mass media initially and it is the reverse of the panopticon, in that the many watch the few. A shift from “Big Brother is Watching You” towards “Big Brother is you, watching” is inevitable. Today, we see that powerful groups such as politicians fear the media’s surveillance of them.

Together, the panoptical and synoptical processes place us in a viewer society in a two-way and double sense. The rapid rise of the synoptical side of this society can create a neutralising effect on panopticism. Scholars view such a potential rise as a method of resistance to digital surveillance and dataveillance. For now, both the top-down and bottom-up surveillance mechanisms seem to be coexisting. Whether one will prevail over the other or both will find their own balance is a question only time will answer.