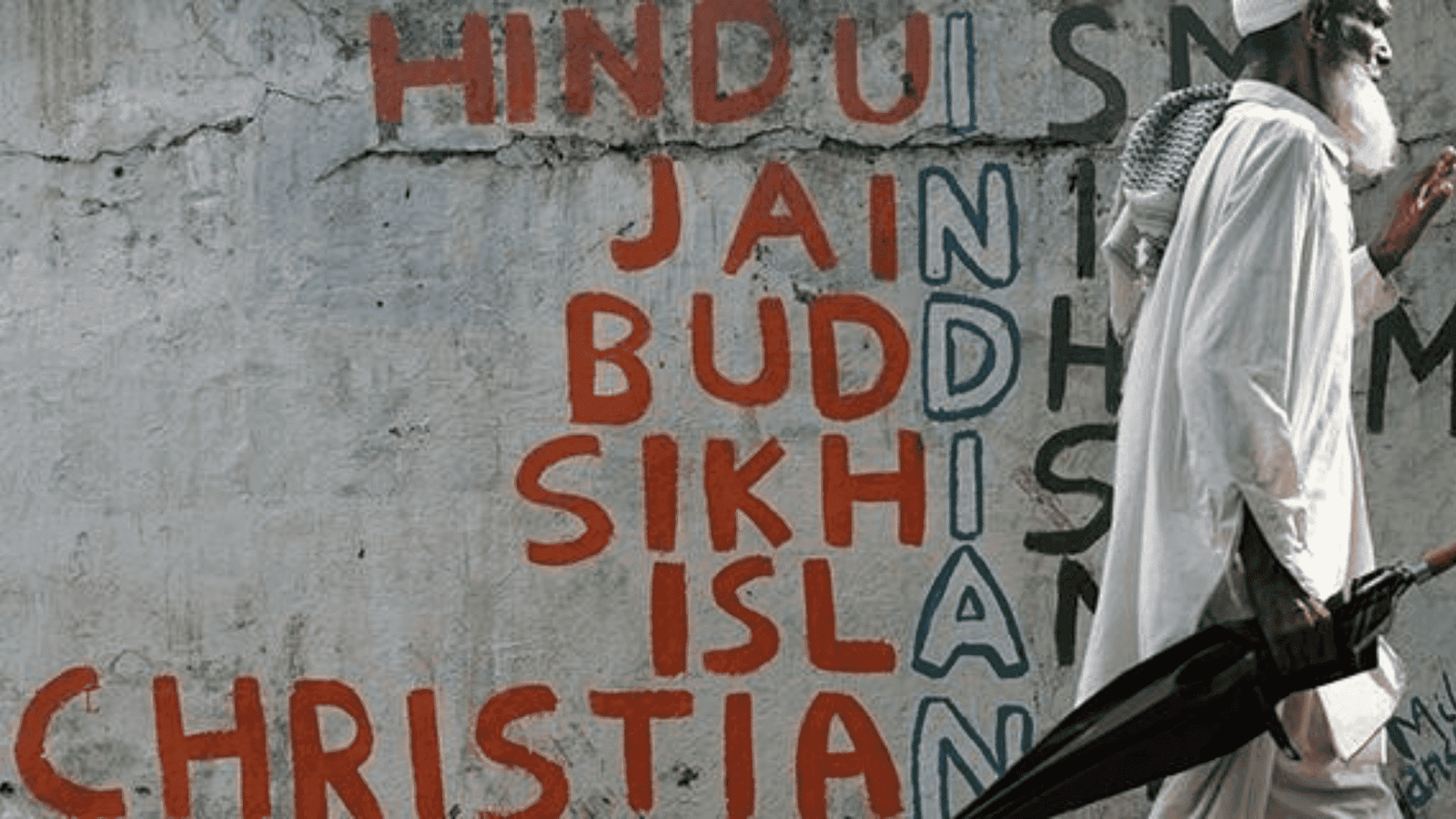

Are the various diversities of India — religious, linguistic, caste-based — being flattened by the rise of Hindu nationalism? Are more and more Indians beginning to believe that Hindus and/or Hindi-speakers are the only true Indians? Is celebrating all kinds of diversities as the founding ideology of Indian nationhood — contained in India’s Constitution and constructed under the combined influences of Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar — coming to an end?

These questions have invited an array of speculations, especially since 2014. But detailed statistics have been hard to come by. We are finally lucky to have the most comprehensive data set yet, summarised in “Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation”, a report published by the Pew Research Center, Washington.

Religion has been studied a lot in India, but mostly in a village or town, or in a small set of them. To my knowledge, until this report came out, there were no nationally representative surveys of religious belief and practice in India. And if they did exist, they, or their findings, were not in the public realm.

Any analysis of what the Pew Research Center finds must begin with the understanding that surveys essentially present data, not explanations, which is left for analysts to develop. Moreover, surveys are snapshots, not historical exercises, and they are an exercise in breadth, not depth. Survey data must be interpreted, and the best interpretations will always be informed by prior modes of understanding and knowledge.

The report uncovers the paradox of Indian identity — that despite the centrality of religion and caste in India’s social and political life, there is a larger “superordinate” civic identity that exists. It is layered on top of the building blocks of caste and religion. India’s freedom struggle sought to create this superordinate identity, and scholars have repeatedly talked about it.

The starting point of the Indian paradox is the high incidence of bonding as opposed to bridging — bonding within one’s religious and caste communities, not bridging across such boundaries. In the 1990s, the bonding-bridging distinction was proposed by Robert Putnam in his exploration of America’s race relations and its civil society.

I had explored the distinction for India in my 2002 book on Hindu-Muslim relations, Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life. More conclusively than any other document I know of, the Pew Center Report shows that most Indians prefer to live in neighbourhoods of their caste or religion; they make friends within their religion and caste; they marry overwhelmingly inside their communities (endogamy), and they want strict prohibition against inter-religious or inter-caste marriages (exogamy). Whether or not this was true to the same extent earlier, a very large proportion of Indians today want religious or caste segregation.

But an overwhelming proportion of Indians (82-88 %) also say that being “truly Indian” means respecting all religions, respecting the army, respecting the country’s institutions and laws, respecting elders, and standing for the national anthem. Region-wise, only in the East (Bihar, Jharkhand, Bengal, Odisha) and Northeast are the proportions lower, but not catastrophically so (70-83 %, instead of 82-88 %). And religion-wise, only Muslims and Christians score lower, but not hugely so (72-81 %).

The report’s findings on Muslims are especially noteworthy. Departing from doctrinal purity, the practised form of Islam in India has syncretistic features. India’s Muslims subscribe to the idea of karma, as much as the Hindus do; every fourth Muslim believes in reincarnation, in the purificatory power of the Ganga, in the multiple manifestations of God; and every fifth Muslim celebrates Diwali. Neha Sahgal, the writer of the Report, and someone who has surveyed Islamic practices in Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Middle East, says that India’s Muslims are closer to Indian Hindus than to Pakistani or Bangladeshi Muslims. And yet, it is also clear that they wish to maintain their identity as Muslims and would like Islamic, not secular, courts to adjudicate upon community matters.

Stated differently, Indians want to be both Hindus and Indians, Muslims and Indians, Christians and Indians, and so on. And such hyphenation, says the report, can be extended to linguistic groups and, to some extent, castes as well. Being an Indian is basically a hyphenated identity. There aren’t too many unhyphenated Indians.

To put the matter comparatively, India is not like France, which allows no hyphens. Indians are closer to the American concept of national identity. According to nationalism theory, France is the ultimate melting pot, not the US, which is a political melting pot, but a cultural salad bowl. The latter concept allows hyphens to exist. Americans are Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Latino Americans, Jewish Americans, Asian Americas, etc. And Trumpian politics reinvigorated an older identity — that of White Americans.

But India’s hyphenation is not yet structured beyond the possibility of rupture. As many as 65 % of Hindus believe that to be a true Indian, you have to be a Hindu, and nearly 50 % believe that to be a true Indian, you have to be both a Hindu and a Hindi speaker. The idea of Hindus or Hindi speakers being equated with India never went this far in modern Indian history.

Will the Hindu-Hindi-Indian equation go substantially further? If it does, then the paradox of having both a Hindu-centric identity and a superordinate civic identity, which respects the Constitution, existing laws, and all religions — simply can’t last. The Constitution is completely against the doctrine that only Hindus are true Indians.

Whether or not this will happen depends on the political process. The survey statistics are not cast in stone. So long as India remains a democracy, pushes and pulls of politics will strengthen or weaken the existing snapshot of reality, which the survey represents.

At this time, South India, says the survey, is leading the charge against politics that equates Hindu and Hindi with India. On all measures relevant to this equation, South India differs radically from Northern and Central India. Parts of the East, as we know, have also joined the pushback.

If this pushback expands its geographical ambit, the Hindi-Hindu-India politics will be weakened, and the superordinate identity will become stronger. If the BJP manages to reverse the pushback, India will be headed towards a breakdown of its superordinate civic identity. Political struggles of the coming years are thus monumentally important.